Systolic vs diastolic pressure explained in detail. Learn the difference, normal ranges, health risks, causes, symptoms, and how to control both blood pressure numbers naturally and medically.

Introduction

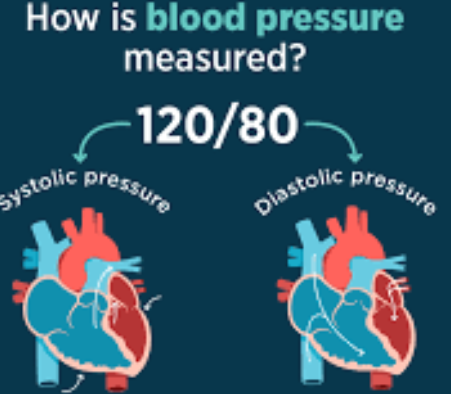

Blood pressure is one of the most frequently measured vital signs in medicine, yet it remains one of the least understood by the general public. When your blood pressure is checked, you are given two numbers—such as 120/80 mmHg—but many people do not fully understand what these numbers mean or why both are important.

This confusion often leads to dangerous misconceptions. Some people believe that only the top number matters. Others assume that feeling fine means their blood pressure is under control. In reality, both systolic and diastolic pressure play distinct and critical roles in cardiovascular health.

This comprehensive guide explores systolic vs diastolic pressure, explaining their biological meaning, differences, normal ranges, risk factors, symptoms, complications, and evidence-based strategies for control. Whether you are a patient, caregiver, or health-conscious reader, this article will help you understand blood pressure at a deeper, clinically accurate level.

What Is Blood Pressure? A Medical Overview

Blood pressure refers to the force exerted by circulating blood against the walls of the arteries. This pressure is necessary to deliver oxygen and nutrients to organs such as the brain, heart, kidneys, and muscles.

Blood pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and recorded as two numbers:

- Systolic pressure (top number)

- Diastolic pressure (bottom number)

Together, these values reflect how efficiently your heart and blood vessels are functioning.

Understanding Systolic Pressure

What Is Systolic Blood Pressure?

Systolic pressure is the pressure inside the arteries when the heart contracts and pumps blood into the circulatory system. It represents the maximum arterial pressure during each heartbeat.

For example, in a reading of 120/80 mmHg, the systolic pressure is 120 mmHg.

Physiological Role of Systolic Pressure

Systolic pressure reflects:

- Heart pumping strength

- Elasticity of large arteries

- Blood volume

- Resistance within blood vessels

As people age, arteries naturally stiffen, which often causes systolic pressure to rise even when diastolic pressure remains stable or decreases.

Normal and Abnormal Systolic Values

| Category | Systolic Pressure (mmHg) |

|---|---|

| Normal | Below 120 |

| Elevated | 120–129 |

| Hypertension Stage 1 | 130–139 |

| Hypertension Stage 2 | 140 or higher |

| Hypertensive Crisis | 180 or higher |

Health Risks of High Systolic Pressure

Persistently high systolic pressure is strongly linked to:

- Heart attack

- Stroke

- Heart failure

- Aortic aneurysm

- Kidney damage

- Cognitive decline

Clinical research shows that isolated systolic hypertension is the most common form of high blood pressure in adults over 50 and is a major predictor of cardiovascular mortality.

Understanding Diastolic Pressure

What Is Diastolic Blood Pressure?

Diastolic pressure measures the pressure in the arteries when the heart is relaxed between beats. It reflects the baseline pressure maintained in the circulatory system.

In a reading of 120/80 mmHg, the diastolic pressure is 80 mmHg.

Physiological Role of Diastolic Pressure

Diastolic pressure is essential because it:

- Maintains blood flow to the coronary arteries

- Reflects peripheral vascular resistance

- Indicates the resting tone of blood vessels

Low diastolic pressure can reduce blood supply to the heart muscle, while high diastolic pressure indicates persistent vascular tension.

Normal and Abnormal Diastolic Values

| Category | Diastolic Pressure (mmHg) |

|---|---|

| Normal | Below 80 |

| Hypertension Stage 1 | 80–89 |

| Hypertension Stage 2 | 90 or higher |

| Hypertensive Crisis | 120 or higher |

Health Risks of High Diastolic Pressure

Elevated diastolic pressure is associated with:

- Increased workload on the heart

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- Coronary artery disease

- Kidney damage

- Early-onset hypertension complications

High diastolic pressure is more common in younger adults and often linked to lifestyle factors such as obesity, smoking, and stress.

Systolic vs Diastolic Pressure: Key Differences

| Feature | Systolic Pressure | Diastolic Pressure |

|---|---|---|

| Heart phase | Contraction | Relaxation |

| Measurement | Peak pressure | Resting pressure |

| Commonly rises with age | Yes | Less common |

| Strong predictor of stroke | Yes | Moderate |

| Strong predictor in younger adults | Moderate | Yes |

Both numbers are important, but their clinical significance can vary depending on age, health status, and underlying conditions.

Why Both Numbers Matter in Blood Pressure Readings

Ignoring either systolic or diastolic pressure can be dangerous. Modern cardiovascular guidelines emphasize overall blood pressure control, not just one number.

- High systolic + normal diastolic = isolated systolic hypertension

- Normal systolic + high diastolic = isolated diastolic hypertension

- Both elevated = combined hypertension

Each pattern carries unique risks and requires tailored treatment.

Causes of Elevated Systolic Pressure

- Aging and arterial stiffness

- High salt intake

- Obesity

- Lack of physical activity

- Chronic stress

- Diabetes

- Kidney disease

- Excessive alcohol consumption

Causes of Elevated Diastolic Pressure

- Smoking

- High stress levels

- Poor sleep quality

- Hormonal imbalances

- High sodium diet

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Genetic predisposition

Symptoms: Why High Blood Pressure Often Goes Unnoticed

Both systolic and diastolic hypertension are often asymptomatic, earning blood pressure the title “the silent force” in the body.

When symptoms do occur, they may include:

- Headaches

- Dizziness

- Shortness of breath

- Chest discomfort

- Blurred vision

- Fatigue

By the time symptoms appear, organ damage may already be present.

How Blood Pressure Is Accurately Measured

Accurate blood pressure measurement requires:

- Resting for at least 5 minutes

- Sitting upright with feet flat

- Arm supported at heart level

- Correct cuff size

- Multiple readings on different days

Home blood pressure monitoring is strongly recommended for early detection.

Diagnosis and Clinical Evaluation

Doctors assess blood pressure using:

- Office measurements

- Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (24-hour)

- Home monitoring logs

Diagnosis is never made based on a single reading.

Treatment Approaches for Systolic and Diastolic Hypertension

Lifestyle Modifications (First-Line Therapy)

- Reduced sodium intake

- DASH or Mediterranean diet

- Regular aerobic exercise

- Weight management

- Stress reduction

- Smoking cessation

- Limiting alcohol

Medications (When Required)

Common drug classes include:

- ACE inhibitors

- ARBs

- Calcium channel blockers

- Diuretics

- Beta-blockers

Medication choice depends on whether systolic, diastolic, or both pressures are elevated.

Can One Be Lowered Without Affecting the Other?

In some cases, treatment strategies can preferentially lower:

- Systolic pressure through improved arterial flexibility

- Diastolic pressure through reduced vascular resistance

However, most therapies influence both values simultaneously.

Blood Pressure Across Different Age Groups

- Young adults: Diastolic pressure more predictive

- Middle age: Both values important

- Older adults: Systolic pressure dominant risk factor

This age-dependent pattern explains why individualized treatment is essential.

Long-Term Complications of Uncontrolled Blood Pressure

Failure to manage systolic and diastolic pressure can lead to:

- Stroke

- Heart failure

- Chronic kidney disease

- Vision loss

- Sexual dysfunction

- Cognitive impairment

Prevention Strategies for Lifelong Blood Pressure Control

- Regular screening

- Healthy diet from early adulthood

- Physical activity habits

- Stress management

- Adequate sleep

- Avoidance of tobacco

Prevention is far more effective than late-stage treatment.

Frequently Misunderstood Myths

- Myth: Only systolic pressure matters

- Myth: Normal diastolic means no risk

- Myth: Blood pressure medications are always lifelong

Clinical evidence contradicts all three.

Future Trends in Blood Pressure Management (2025 and Beyond)

- Personalized medicine

- Wearable blood pressure technology

- AI-assisted risk prediction

- Lifestyle-first treatment models

Important

Understanding systolic vs diastolic pressure is essential for preventing cardiovascular disease, improving longevity, and maintaining overall health. These two numbers represent different phases of the heart’s activity, yet they work together to define your circulatory status.

Ignoring either number can result in delayed diagnosis and irreversible damage. With regular monitoring, informed lifestyle choices, and appropriate medical care, both systolic and diastolic pressure can be effectively managed.

Blood pressure is not just a reading—it is a lifelong health indicator.

FAQs

1. What is the main difference between systolic and diastolic pressure?

Systolic pressure measures the force of blood against artery walls when the heart contracts, while diastolic pressure measures the pressure when the heart relaxes between beats. Together, they show how efficiently the heart and blood vessels are functioning.

2. Which is more dangerous: high systolic or high diastolic pressure?

Both are dangerous, but high systolic pressure is more strongly linked to heart attack and stroke, especially in older adults. High diastolic pressure poses greater risk in younger adults and can damage the heart over time if untreated.

3. What are normal systolic and diastolic blood pressure ranges?

Normal blood pressure is considered below 120/80 mmHg. A systolic reading under 120 and a diastolic reading under 80 indicate healthy blood pressure levels.

4. Can systolic pressure be high while diastolic pressure is normal?

Yes. This condition is called isolated systolic hypertension, common in adults over 50, and is mainly caused by stiffening of the arteries. It significantly increases the risk of stroke and heart disease.

5. Can diastolic pressure be high while systolic pressure is normal?

Yes. This is known as isolated diastolic hypertension, more often seen in younger adults, and is usually linked to stress, obesity, smoking, or poor lifestyle habits.

6. What causes systolic blood pressure to increase with age?

As people age, arteries lose elasticity and become stiffer, causing systolic pressure to rise. Reduced physical activity and long-term dietary habits also contribute to this increase.

7. What symptoms occur when systolic or diastolic pressure is high?

Most people experience no symptoms, which is why high blood pressure is called a “silent condition.” When symptoms do occur, they may include headaches, dizziness, blurred vision, chest pain, or shortness of breath.

8. Can lifestyle changes lower both systolic and diastolic pressure?

Yes. Healthy diet, reduced salt intake, regular exercise, weight management, stress control, good sleep, and avoiding tobacco can effectively lower both systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

9. Does medication lower systolic and diastolic pressure equally?

Most blood pressure medications affect both numbers, but some may have a stronger effect on either systolic or diastolic pressure depending on the drug class and individual health profile.

10. How often should blood pressure be checked to monitor systolic and diastolic levels?

Adults should check blood pressure at least once a year, while those with elevated or high blood pressure should monitor it more frequently—often weekly or daily—using home blood pressure monitors as advised by a healthcare provider.